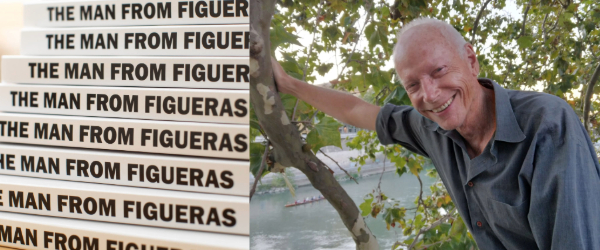

VCU’s dance master Chris Burnside tells his life stories in "The Man from Figueras"

April 16, 2025

For most of his adult life, Chris Burnside’s creative language was kinetic movement. The choreographer and former Chair of VCU’s Department of Dance and Choreography (1991-1996) expressed himself through dance. Now, in the seventh decade of his life, he’s turned to a new medium–the written word. His memoir, The Man from Figueras, is newly published on Scholars Compass and also available in a limited edition printed book.

Why write a book? “I feel like I’ve had a really good life. I feel appreciative of how I have lived and what I did,” Burnside said. As he lived, he reflected upon experiences along the way and teaching “was an arena to filter learning experience for me or make adjustments in my perceptions. … After I retired and stopped performing, there was no arena for seeking that meaning or learning.” A close friend, who had heard Burnside’s life stories over years of conversations, convinced him to write them down. “I didn’t think of myself as a writer. I had told stories as a dancer.”

In dance, he had combined the narrative of stories–about his brief, horrible stint in the stateside Army during the Vietnam War, for instance– with movement. He developed several short movement monologues and several evening-length monologues. All used the same strategy: He wrote a script for the spoken part and married all the words to movement or gesture so he could navigate the performances. His choreography often included spoken words but they were paired with the physical, gestures or shrugs or shudders or jumps. “I had to marry every single word to movement.”

But now, the words stand alone in book form. The style of storytelling in The Man from Figueras was inspired in part by Spalding Grey, known for autobiographical monologues that he wrote and performed for the theater in the 1980s and 1990s. Burnside, who called himself “a natural storyteller,” had seen Grey perform in Belgium and later met him when he appeared in Richmond. “He was a trained actor and he was comfortable telling stories extemporaneously. I couldn’t do that.” So, Burnside wrote a story, memorized it and then built a dance to tell the story.

Routinely, Burnside did not chronicle his memories in writing. He remembered them. He did not keep a journal or diary although some of his chapters are packed with detail. He admits to having a near-photographic memory. And he would reflect, recite stories to others and use the experiences in performances.

“I had the kind of memory that when something struck me as out of the ordinary or I was learning something, it was very clear to me. I never forgot those moments.”

His life has been full of such memorable moments, some of which are shared in his book. He writes about his arrival to study art at Richmond Professional Institute, the precursor to VCU, as a homecoming of sorts. Surrounded by wonderful teachers and creative souls like himself, he found a home and thrived.

Living in Los Angeles in the 70s, he describes watching the formidable dancer Bella Lewitzky rehearsing as “the beginning of me learning what the dance art form was about.”

He writes: “She was showing me a progression that locomoted across the space. She was like a piston engine—just flying. All of a sudden, I didn’t see her lines or shapes, I just saw her moving. HOW she was moving, the phrasing of it, the speed of it, the dynamic range of it. AND in addition, trailing behind her was an afterburn like a contrail. And I … actually could see it. It was like she was literally drawing in space.”

The book’s title comes from the memory of a rather surreal moment where he made eye contact with his doppelganger on a street in Figueres, Spain. “As we walked along the cobblestones an old man was coming toward us. As we passed, I noticed his eyes. They were light in color and the eyelids and the skin all around the eyes were lavender and white. Like mine. In many other ways he looked like me as well. But I was in my early forties, at the height of my dancer’s physicality, and he looked to be in his late eighties. Immediately after passing him, I stopped and turned around. He had done the same and was staring at my eyes. It felt like I was looking at myself in another forty years. As we continued to stare, his eyes filled with tears and I realized that mine had too. After a moment, we both turned away and walked on—into our lives.”

Burnside attended Richmond Professional Institute as an undergraduate, earning a BFA in communication arts and design in 1969. In 1973 he received a master’s degree in dance from Florida State University, which led to a professional career performing across the country and in Europe. He returned to VCU to teach in the Department of Dance and Choreography in the VCU School of the Arts from 1985 to 2005. He served as chair of the department for five years and retired in 2005.

The book brims with people who crossed his path, some in influential ways–such as beloved and visionary professor Richard Carylon–and others who were bit players, namely Henry Kissinger and Dustin Hoffman.

A constant beat through the 90 stories divided into decades of life, are insights about learning and teaching. He writes about first teachers, good teachers and bad ones. What did he learn about teaching from being taught? Reflecting on those experiences, he said, “I’ve often said to my students, ‘I’m not your teacher. You are your teacher. I’m a facilitator. … I’m here. … I want to help you find your voice and as long as you're passionate about it and engaged with it, then my job is done.’ I feel if you as a teacher can help someone open their voice, help them get permission to create that was a great gift. I gave myself permission to follow my voice and I thought that was the best gift I could give an emerging creator, an artist. “

When writing about one’s life, one of the many choices the writer must make is what not to write about. Widely respected in dance circles, Burnside, who is named in hundreds of reviews and who has graced the cover of national and international dance magazines, writes very little about his own fame, celebrity or artistic achievements.

Known in Richmond and the VCU community for activism in the gay community, he doesn’t write about his own coming-out or pivotal role as an advocate for VCU’s gay students and a founder of what is now Equality VCU and namesake of the Burnside-Watstein Awards. He mentions only briefly the AIDS crisis, a defining era in his lifespan. Recounting the death of one friend, he writes: “AIDS decimated our generation, taking the most beautiful and talented men. Dance and other performing arts were especially hard hit. For those of us left, it has been a lifelong lamentation.”

As for the choices about what not to write about, Burnside reflected, “I didn’t want to be preaching about anything. And I also wanted this book to have an uplifting feel, that anyone reading the book would feel included. I don’t think it was a cognitive decision about excluding things. I hope the book is kind of a universal book.”

< Previous Next > Chat

Chat